Orange County Produce

Orange County Produce

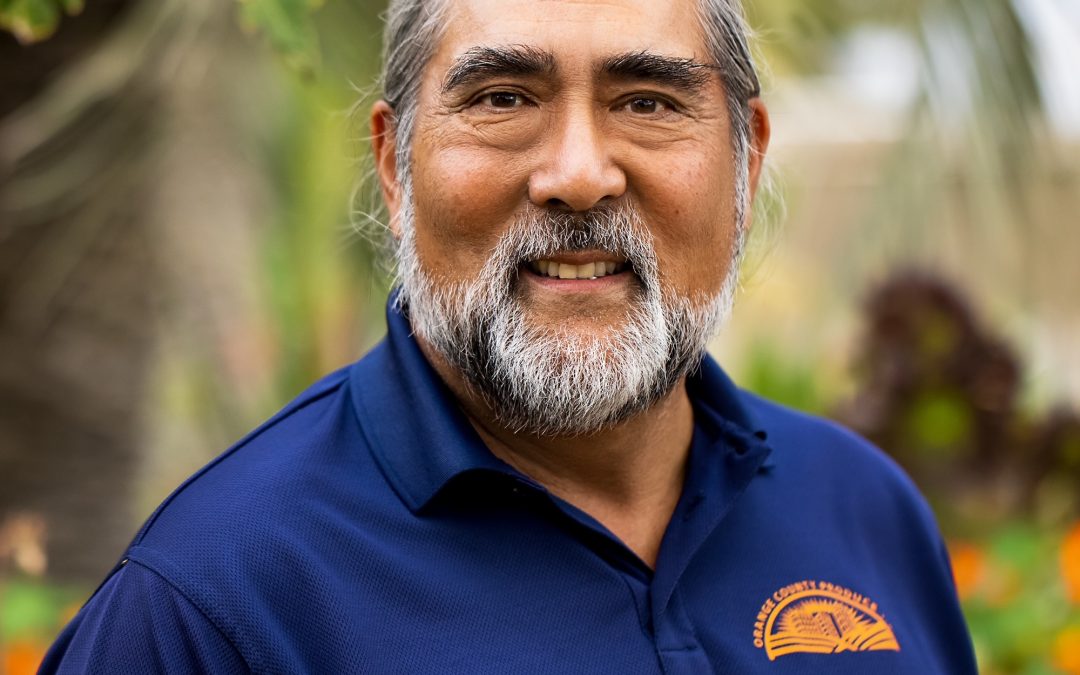

A.G. Kawamura, Orange County Produce. Credit: A.G. Kawamura

“

A.G. Kawamura

Orange County Produce

Website: https://ocproduce.com

Southwest Region | Irvine, CA

Main Product: Vegetables

Scale: 1000 acres under management

Urban soils restoration, precision mgt., growers’ network.

When A.G. Kawamura heads out each morning to check on his crops, his route is an unusual one for a vegetable grower. He drives into residential developments, onto military bases and through city parks, schools and abandoned orange groves to get to his fields. His family didn’t set out to be urban farmers, but they started farming early enough and stayed in business long enough that the city eventually grew out to reach them. “We are definitely urban producers or farmers in an urban area,” A.G. says. “It was a rural area when we started farming here. The city came to us and then it surrounded us. We’ve just never left.”

A.G.’s grandparents came to southern California from Japan around the turn of the last century and made their living in the agriculture of their new home. They did whatever work they could find in those early days, one set of grandparents picking and packing oranges, sharecropping and landscaping, and another grandparent starting a small fertilizer and farm supply company. After the Kawamura families were released from an Arizona internment camp in 1945, they returned home to the Los Angeles area to rebuild their lives. Over a decade later, the family moved farm operations to Orange County, growing and shipping produce in the area, which was well-known at the time for growing oranges, walnuts, tomatoes, lima beans, asparagus, along with other vegetable and horticulture crops.

As the area population grew, rising costs and skyrocketing real estate prices forced many Orange County growers to sell out. Those that remained continued to grow on ground leased from several large private landowners and military bases. “We don’t own any of the ground we farm on here in the county,” A.G. explains, “and that’s a challenge because we rent ground from the utilities, from a school district, from cities and counties, from the military and from private developers. We will farm any vacant lot that’s over four or five acres. If I can see the weeds are growing well, and I can see that there’s a fire hydrant or recycled water connection nearby, then we look at those as viable places to farm.”

Want to read more? You can find the full version of this story in the Second Edition of Resilient Agriculture, available for purchase here.

Recent Comments